A Failed Experiment Never Fails!

- Yathish Achar

- Dec 27, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 28, 2025

Most experiments fail. What defines a researcher is not avoiding failure, but staying long enough to understand it.

On a sunny afternoon of June 28, 1968, in Berkeley, a scientist was setting up an experiment to understand why DNA rings isolated from bacterial cells were always negatively supercoiled. By the late 1960s, it was fairly well accepted that DNA in a living organism exists in three supercoiled forms: negatively supercoiled, positively supercoiled, and relaxed DNA. The major difference among these forms was the number of base pairs per turn.

The famous Watson–Crick double helix model explains DNA in its relaxed form, where approximately 10.4 nucleotide bases are present per turn of the helix. If the number of bases per turn goes below this magic number, then it is called positively supercoiled, whereas if it increases, it becomes negatively supercoiled. Barring a few exceptions, most DNA isolated from natural sources always tends to be negatively supercoiled. This is what he wanted to understand. Why?

Like any other day, he lysed the bacterial cells and set up the centrifuge for the next step. Suddenly, his office phone rang. It was his wife, Sophia. She called to tell him that their elder daughter, Janice, was down with a high fever and that he should come immediately to take her to the pediatrician. He was in a dilemma. We all have been in that situation at least once, where we cannot ignore family responsibilities, but at the same time cannot simply discard an experiment midway.

He decided to keep the centrifugation running until he returned from his fatherly duty. Originally, the centrifuge was supposed to run for 20 minutes, but he managed to return to the lab only after two and a half hours! Nevertheless, he went ahead and completed the experiment, and to his surprise, most of the rings he found were relaxed instead of negatively supercoiled. He had never expected this observation, nor had he seen this before.

Anyone in his place would have discarded the experiment, saying, “I might have done something wrong in a hurry,” and so on. It is easier to repeat an experiment than to decode a failed experiment. But not him. He decided to understand the reason behind it. His first suspect was the increased centrifugation time, but he quickly ruled that out. He decided to repeat the experiment according to the original protocol. Again, like previous times, he obtained negatively supercoiled DNA rings.

He started to scratch his head-what might have caused negatively supercoiled DNA to convert into a relaxed form? He again went through each step carefully. This time, he found a problem in the experiment he had conducted on the day he received the call from home. In a hurry, he had forgotten to adjust the temperature setting to 0 °C, the temperature at which the centrifuge was intended to run. Unlike modern centrifuge equipment that comes with flashy LCD screens and push buttons, older centrifuges required the temperature to be adjusted using a small screwdriver!

When he returned that evening, the temperature had reached more than 20 °C instead of 0 °C. Was temperature the cause of this change? He had no reason to believe so, but he decided to test the hypothesis. The next time, he carried out the experiment at 20 °C instead of 0 °C. Bingo! He obtained similar results-most of the DNA rings were relaxed instead of negatively supercoiled.

It took him another year to understand and characterize the reason responsible for these alterations. He discovered that a single protein present in bacteria was responsible for this change. He submitted his findings to the Journal of Molecular Biology in July 1970. It was difficult for the editor and reviewers to comprehend the findings. After several rounds of correspondence, the journal accepted the manuscript in 1971.

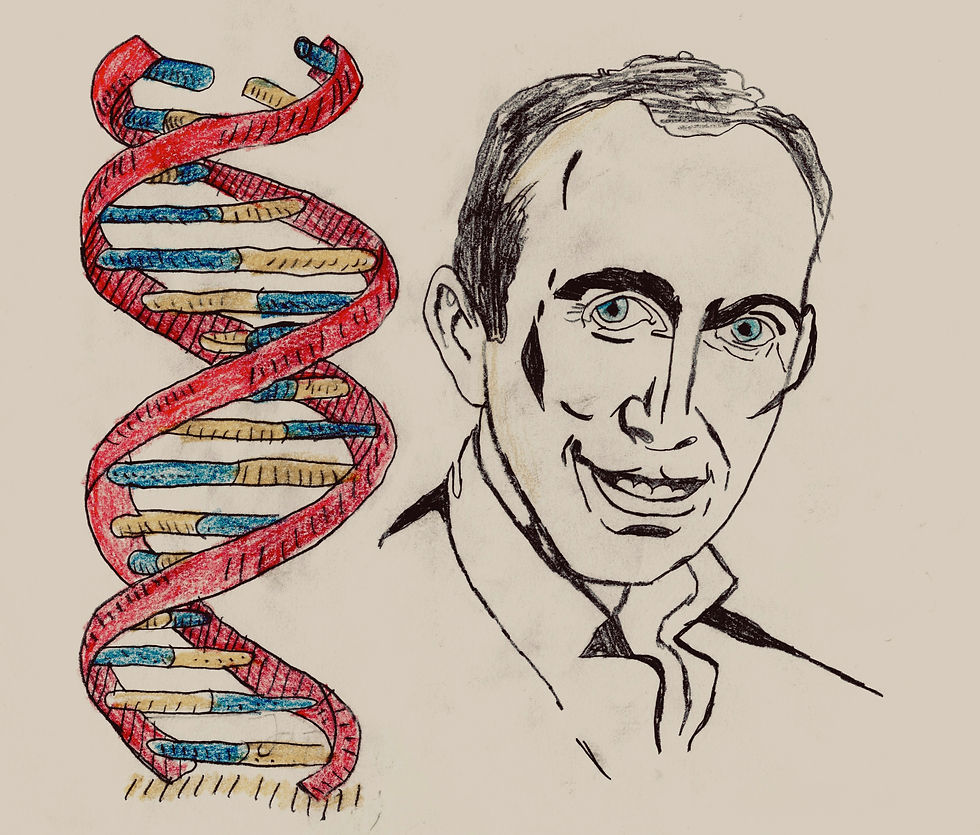

Art Credit: Diyansh Y. Achar

The question here is: how many of us modern-day researchers would have followed his steps to decode the reason behind the failure of the experiment at the very first instance? My bet is-not many! It is easy to accept defeat, go home, switch off your mind, and get up the next morning to give a fresh start to the experiment.

If you think your experiments are failing too often, you are not alone. Every experiment fails-that is the reality. How you face it and what you learn from it makes you the researcher. Researchers in their early careers tend to face a higher proportion of failures, but as they gain experience, this proportion of failed experiments comes down and the proportion of successful experiments rises. Overall, it is common for 60–80% of experiments to fail in the early part of a research career.

Whatever the reason-technical problems, biological variability, a horrible hypothesis from the mentor, a wrong protocol, wrong colleagues, a horrible breakfast, or maybe the experiment simply decided to have fun by ruining your day-you can make as many reasons as there are stars in the sky. The point is that failure is the biggest part of research life. It enters the lab with us every day. It sits right next to us. It is with us when we plan experiments. It sits beside us during seminars, coffee, and lunch breaks. And finally, it even occupies the side portion of our bed, staring at us while we stare at the ceiling, thinking, “Why are none of my experiments working?”

It is as if “failure” and we come to an agreement at the beginning of our research careers: let us walk together, hold hands, and remain companions throughout the journey.

Ask a young student who is about to join research how they will face failures, and their answers will be pleasing-as if they and failure grew up together and failure is going to listen to them! But once the journey starts, we begin to hate our companion. We do not want to sit with failure anymore; we want to get out of this relationship. This is the problem.

You feel hopeless as the mountain of failures starts to stare at you day in and day out. You feel targeted, and you just want to run away from failures. The research question you once liked, the amazing hypothesis that made you fall in love with research, starts to feel like a burden. You question your choices. You imagine that your failures will somehow magically disappear and that your experiments will suddenly start to work. The question is: how long can you keep hoping for this, and more importantly, how much motivation is left in your tank to get up in the morning and face the same failure again?

Eventually, small rays of sunshine begin to appear amidst the dark clouds. You always find a way-either you find a solution to the problem, realize that you are approaching it in the wrong direction, or decide to completely omit the problem. The important thing is that you always find a way. The only question is whether you hold on long enough to reach that point.

Some might lose motivation and give up on research altogether. They just want to finish for the sake of the degree, for the paper, or simply hang on until alternative career options pop up.

Research is the only field that pays you to make mistakes and learn from them. Somewhere between repeated failures and quiet persistence, we start to listen more carefully-to the data, to the system, and to our own assumptions. Failures slowly stop feeling like enemies and begin to resemble teachers. Over time, we realize that research does not reward those who avoid failure, but those who learn to stay with it long enough to understand what it is trying to say. And that is why a failed experiment never truly fails-it simply asks us to look a little deeper.

By the way, the scientist who had to interrupt his experiment due to a family emergency was James C. Wang, and the protein he identified was named ‘ω’ (Omega) in the beginning, which is now popularly known as DNA Topoisomerase I.

---